The photographer Felice Beato arrived in Yokohama in 1863, only nine years after Japan ended nearly two centuries of isolationism. Adventurous and entrepreneurial, Beato was undaunted by what he found there: travel restrictions, a meager tourist economy, and even skirmishes with rogue samurai. Yet, over the next decade, Beato developed a foreign clientele clamoring for his photographs.

The photographer Felice Beato arrived in Yokohama in 1863, only nine years after Japan ended nearly two centuries of isolationism. Adventurous and entrepreneurial, Beato was undaunted by what he found there: travel restrictions, a meager tourist economy, and even skirmishes with rogue samurai. Yet, over the next decade, Beato developed a foreign clientele clamoring for his photographs.

A naturalized British citizen, Beato was born in Venice in 1832. As a youth, he moved with his family to Corfu and then Constantinople, where he began his career. From 1855 to 1857 Beato worked with the British photographer James Robertson in the Middle East and the Crimea before embarking on his own spectacular career photographing the Indian Mutiny in 1858 and the Second Opium War in China in 1860.

“My house is inundated with Japanese officers who come to see my sketches and my companion Signor B-‘s photographs,” wrote the British artist Charles Wirgman from Yokohama on July 13, 1863. For the next decade, Beato’s innovative work set the standard for photography in Yokohama, the primary port for tourists. Yet, despite his success, Beato left Japan penniless in 1884 due to heavy losses on the Yokohama silver exchange. He may have even fled Japan to avoid jail! Too resourceful to be undone, Beato began again in Burma. In the end, Beato returned to his homeland and died in Florence on January 29, 1909.

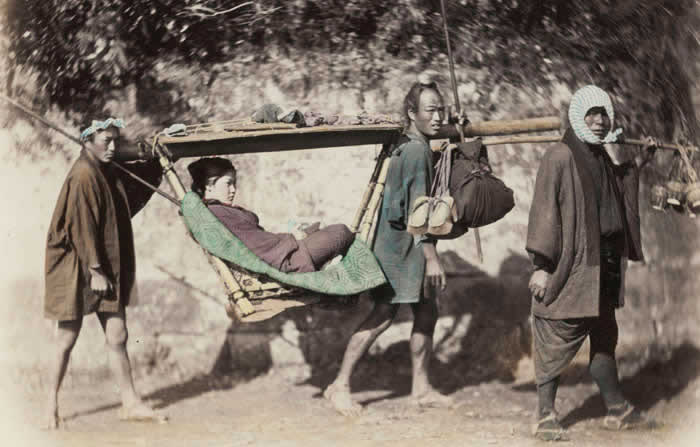

What made Beato’s photographs of Japan so innovative? So exciting for Westerners? Gigantic Buddhas and ornate temples, proud samurai and elegant geisha—these were the same subjects found in coveted Japanese woodblock prints. Beato also hired Japanese artists to paint the photographs. Though Japan embraced a future of modernization, Beato’s artful photographs offered a peephole onto the past—an exotic, feudal Japan.